Trailer Park Fae is a faintly ridiculous book. “Faintly” is perhaps too mild a qualifier: I have rarely read a book that inspired me to so many disbelieving snorts.

If I may be permitted a comparison, however, the same was true for the film Jupiter Ascending. And like Jupiter Ascending, despite my baffled raised eyebrows and choking coughs of really? I found Trailer Park Fae to be reasonably enjoyable.

Trailer Park Fae is the first novel in Lilith Saintcrow’s latest urban fantasy series. Jeremiah “Jeremy” Gallow is a construction worker. His beloved wife died in a car accident some time ago, and his home is in a trailer park. But Gallow has a past: he used to be known as Gallowglass, the half-human armsmaster to the Fae Queen of Summer, before he fell in love with a mortal and walked away from the faerie court.

Robin “Ragged” is part of Summer’s court. Half-human, like Gallow, she’s a magic-worker and a messenger, whose voice can kill, if she lets it, if she loses control. Sent as a messenger to the mortal realm to retrieve something from a human on behalf of the Summer Queen, she finds herself hunted by riders from Unwinter, Summer’s rival court. Gallow’s intervention helps save her life, and results in a mutual fascination. For Robin, Gallow’s involvement — for no gain to himself — is inexplicable, while for Gallow, Robin bears an uncanny resemblance to his dead wife. Both of them are soon to be caught up in a struggle over the faerie realms.

There is a disease that affects the fae, though not the half-human ones. It has primarily affected the fae of Unwinter. The ruler of Unwinter believes that it is Summer’s doing, while the word in the Summer realm is that Unwinter was treacherously responsible. Not all the fae are affiliated with the separate realms: some are free fae, and their leader is Puck, the Goodfellow. Summer, Unwinter, and Puck are playing each other off, one against another, and Robin and Gallows are tangled up in between. They both have secrets, dangerous ones, and neither can trust the other — although they want to.

Saintcrow’s faerie realms owe much to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Faerie Queen, salted with the usual odd bits and pieces of folklore from north-western Europe (sidhe, check; night-mares, check; kobolds, check; hobs, check). Her prose, too, is liberally inflected with Shakespearean rhythms, or at least with a cadence and an eye for imagery that approaches the flamboyant. Let us not use one adjective when two will do! The dialogue is most often stylistically formal, self-consciously archaising in its rhythm and structure without ever quite moving wholly into an archaic mode, or using the grammatical peculiarities of early modern English: the dialogue is in a style that possesses the sensibility of no particular historical period and yet rejects, nonetheless, modern conventions.

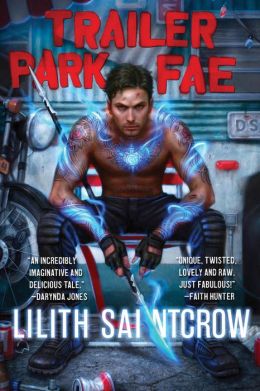

I confess myself in no small measure annoyed by this particular choice. It tries my sense of the ridiculous the most — and in a novel advertised by a cover starring a shirtless bloke (one who’s obviously suffering from lava-balls, poor man) with glowing tattoos, a pointy stick, and artistically tousled hair, I fully expected I’d have to have my tolerance for the ridiculous set to max.

This really isn’t my sort of book. It’s readable, don’t get me wrong, and enjoyable in an eyebrow-lifting sort of way. Stuff happens. People brawl and emote and discover they are long-lost relatives — possibly with the hots for each other. There are pretty sentences. But aside from my minor irritations with its style and with the worldbuilding, I have one major problem with Trailer Park Fae: I find all its major characters really rather blandly uncompelling. If I hadn’t agreed to read it for review, I would have said Jo Walton’s Eight Deadly Words (“I don’t care what happens to these people”) and put it down to go make a cup of tea.

Not every book, sad to say, is for every reader.

Trailer Park Fae is available June 23rd from Orbit.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.